Correction: The original version of this story used an estimate for the number of enslaved people in St. Louis provided by the Slavery, History, Memory and Reconciliation Project. After this story was published, the project clarified that the number it provided captured the number of people enslaved across the Missouri Province, which includes not only the city of St. Louis but also other states, including Louisiana, Kentucky, Alabama, Illinois and Kansas, and smaller parts of others. We’ve updated the story to reflect that distinction, and also add a number specific to the number of enslaved people in the city of St. Louis based on research from Dr. Kelly Schmidt, postdoctoral research associate at Washington University. The headline has also been changed to reflect this number. These updates provide a more accurate range of people known to be enslaved by the Jesuits in this area. These numbers will continue to change over time as research continues and we will continue to update this story accordingly.

ST. LOUIS – Against their wills, Thomas and Mary Brown, Moses and Nancy Queen, and Isaac and Susan Hawkins were taken from a White Marsh, Maryland, plantation in 1823, forced to leave their families and children 800 miles behind to help the Jesuits in their founding of the Missouri Mission.

Enslaved people were essential to what Jesuit institutions in St. Louis would become. The Jesuits moved another 16 to 18 enslaved people to St. Louis from Maryland in 1829, the same year the Society of Jesus took over St. Louis College, known today as St. Louis University.

Nearly 200 years later, descendants of people the Jesuits enslaved are learning and reclaiming the stories of their ancestors and pushing the institutions around them to tell a complete story, one that includes their families and the harm that was done.

“I believe souls can’t rest until fundamental wrongs are done right,” said Rashonda Alexander, one of the descendants.

“I believe souls can’t rest until fundamental wrongs are done right,” said Rashonda Alexander, one of the descendants.

Alexander is a descendant of Jack and Sally Queen, who were a part of that second group that relocated to St. Louis. Up until 2020, Alexander, like many Black Americans, was not able to trace her family earlier than a certain point in time.

“I kept hitting a brick wall with my great-great-grandfather,” she said. After years of searching, a visit from a stranger would bring her many of the answers she was seeking.

“A reporter knocked on my door, at the house, and he said, ‘I believe that you are a descendant of persons owned by the Jesuits.’”

For Alexander, this revelation inspired more investigation. She not only now knew she was a descendant of enslaved people owned by Jesuits; she also had to reckon with her own history as a 2002 graduate of St. Louis University – which benefited from owning human chattel, including her ancestors.

“I attended the university my ancestors built for free,” said Alexander, who also identifies as a “cradle catholic,” essentially meaning she had practiced the Catholic faith since birth. “I kept thinking, ‘Are we walking on their bones?’, ‘Are we walking on their blood?’, ‘Did I walk past somewhere where they were beaten?’”

Across the country, other people have come to discover and question the church’s role in their families’ stories, as the Society of Jesus, a Roman Catholic order of priests and brothers, and affiliated organizations inside and outside of St. Louis have started to examine its history more closely.

Some institutions have launched research initiatives to explore their beginnings more deeply, while others have created foundations to further the work. Still, some descendants say, there is more work to be done; acknowledgement is only the beginning.

This contract lists the names of the first six enslaved people moved from White Marsh, Maryland to Missouri. Photo via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

There is a long history of Jesuits around the world owning slaves, according to Fr. Jeffrey Harrison, SJ, the project coordinator for the Slavery, History, Memory and Reconciliation Project in St. Louis, a research initiative involving the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, St. Louis University and the St. Louis African American History and Genealogy Society. It’s a practice that predates both America’s independence in 1776 and the first record of slavery in the territories in 1619, according to Jesuit archivists.

“Almost from the beginning we engaged in some forms of human slavery,” Harrison said.

Ignatius Loyola founded the society, which would come to be known as the Jesuits, in 1540, when Pope Paul III officially approved the organization. In the United States, Jesuits went on to own slaves in Missouri, Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, Kansas, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Maryland until slavery was ruled unconstitutional in 1865, according to their own records. Institutions of higher education benefited from slave labor — those that exist today, including St. Louis University, Georgetown University and Spring Hill College, as well as others that have since closed their doors. But Harrison said the quest to uncover one’s history is not just happening in St. Louis, it is an experience shared by descendants across the country.

In Maryland, Robin Proudie said she remembers how she felt the day she found out her lineage was intertwined with the Jesuits. Her notice came in the form of a letter.

“The Society of Jesus explained to me that through research that they found that I am a descendant of Henrietta Mills,” she said.

Details about Henrietta Mills’ life can be pieced together through records from the Jesuit Archives, housed in a building in the Central West End neighborhood in St. Louis. They show Mills was 16 when she married 20-year-old Charles Chauvin on June 28, 1860. On the same sheet of paper as her and her husband’s names are listed another four words: “slave of St Louis University.”

Robin Proudie visited St. Louis University ‘s current campus in November of 2021. Courtesy photo.

Mills and her husband went on to have 10 children between 1860 and 1884, and became godparents to three more. When the Civil War erupted, Charles was drafted into the U.S. Colored Infantry. His name today is listed at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington D.C., correcting a history that “ignored the heroic role of 209,145 US Colored Troops in ending slavery and keeping America united under one flag,” as the memorial’s website states.

Proudie, originally from St. Louis, moved to Maryland later in life, not knowing she was moving to the state from which her ancestors were forcibly driven nearly two centuries ago. That piece of paper sparked a yearning to find out more and eventually Proudie would not only go on to find more information about Henrietta Mills but also her “brothers and sisters and siblings and mother and grandparents.” In the process she met other descendants like Alexander, whom she now affectionately calls cousin.

“It’s been a joy to see, you know, that we share this history,” she said.

For researchers, pinpointing a solid total number of the people the order enslaved is difficult. Sacramental records held by the Jesuits, however, help provide a snapshot for certain areas. In 2016, the New York Times spotlighted Georgetown University’s links to enslaved people — including, according to a 1838 bill of sale, the sale of 272 enslaved people to stay afloat.

In the Missouri Province, “we’ve come up with a number of about 200 over time that were either directly owned, rented or hired,” Harrison said in reference to the number of people the Jesuits owned between 1823 and the end of slavery. The province included sites of enslavement in Louisiana, Kentucky, Alabama, Illinois, Kansas and others. However, according to Dr. Kelly Schmidt, postdoctoral research associate at Washington University and primary researcher on this project, the number of people the Jesuits enslaved in St. Louis over time was at least 70.

These records include documentation of marriages, baptisms and deaths, creating “a bit of a giant jigsaw puzzle that you have to try to match up” Harrison said. These records helped break through the “1870 brick wall,” which refers to the difficulty that comes with tracing the lineage of African American families preceding the abolition of slavery; the 1870 census is the first census to list the names of African Americans alongside the rest of the population, and is for many it is the first official notation of surnames for formerly enslaved people.

Peter Hawkins was the first child born to an enslaved couple in the Missouri Mission. Photo via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

Bursting through that brick wall filled in a lot of gaps for Rashonda Alexander’s family. Over the years she said her family has always been asked both why they were raised in the Catholic faith and also how they got to St. Louis. Now, she finally has answers.

“We were brought forth from up north by the Jesuits,” she said. “So all of it was connecting dots and it was really inspiring.”

Recognizing history

Tracking down descendants of those the Society of Jesus enslaved is an endeavor carried out by organizations across the country including the Descendants, Truth & Reconciliation Foundation, a nonprofit that “works to mitigate the dehumanizing impact of racism on our human family while dismantling the continuing legacy of slavery in America through truth, racial healing and transformation,” according to its website. Its founding partners consist of both descendants of enslaved people the Jesuits owned at Georgetown University and members of the Jesuits, including former president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, Fr. Tim Kesicki, SJ and current executive director, Campaign for Descendants Truth and Reconciliation Trust and Foundation.

“This is much bigger than Georgetown University,” Kesicki said.

Joe Stewart, a founding member of the foundation and a descendant of enslaved people owned by Georgetown, said this is the reason this story must continue to be told. “When this first broke in the New York Times, there was no mention of the descendants who were in the St. Louis area and we later became aware of that,” Stewart said, referring to media coverage of Georgetown’s sale of enslaved people.

The foundation, as Stewart described, has a goal to be transformative in its quest to “engage in our work of racial healing in America.”

“It has no geographic boundaries. It has ancestry connections. And that’s the only connection, not by boundaries, not by geography, but by blood line to those people that’ve been identified as ancestors of those enslaved by the Jesuits,” he said.

Amplifying the stories of descendants across the country and specifically in St. Louis is something Robin Proudie said is at the core of all of her work since learning of her lineage. In early November she returned to St. Louis, where she took a tour of St. Louis University. She could feel the presence of her ancestors, she said.

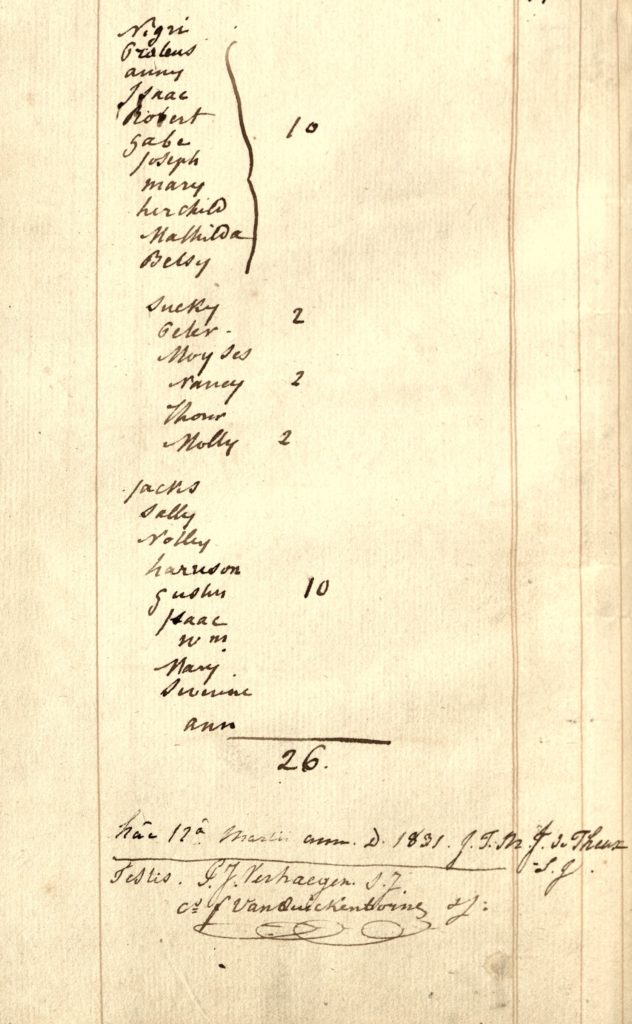

Treasury entry listing some of the names of the people the Jesuits enslaved in Missouri, including Jack and Sally Queen. Photo via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

“It just made me feel proud and it made me feel angry because they’re not acknowledged, you know, they’re like nameless souls,” she said.

Proudie said that mix of feelings is what drives her and her family to not only keep digging but also to demand the story be told in full.

“We want to ensure that every student that walks through those doors understands that the education that they’re getting came off the backs of our ancestors,” she said.

Still, she says, the work can’t end with acknowledgement – though she believes a formal apology is due. Reconciliation for her looks like, as she puts it, reparative justice. “I want to honor and commemorate my ancestors for the forced labor that helped to build and sustain these institutions, I want them to be recognized.”

For that to happen, she says, there would need to be first “commemoration and honor, then education and then third, repairing the damage done to my bloodline, to my family to help close the racial wealth gap.”

She said part of that does include compensation and further economic empowerment. To move the mission forward, Proudie said she and other St. Louis descendants meet regularly in what they call the Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved.

“We have several initiatives that we’re going to ask people to support us in and bring this history to the public for generations to come,” she said.

“Say their names”

Part of Proudie’s work is making sure the stories of the enslaved are never forgotten, an effort also shared by Dr. Katrina Thompson Moore, an associate professor in the departments of history and the department of African American studies St. Louis University.

“A lot of older works showed slavery as this paternalistic loving institution and it wasn’t until you have more diverse, more Black people doing research and more people saying, ‘hey, we simply can’t be true,’” said Moore, who is also the undergraduate director of the history department.

Moore was part of early conversations between St. Louis University and the Jesuit Archives, which are separate entities, about how to move forward in acknowledging Jesuit involvement in slavery — and further, how St. Louis University benefited from it. For her, the intention had to go beyond just dialogue.

“This is my objective personally as a historian, first, as a Black person who’s a descendant of slaves. If I had known anyone’s name that survived the middle passage and lived through those tumultuous times for generations, I’m going to say their name,” she said. “I’m going to tell their stories, no matter if it’s just one or two sentences of their story and the fact that we’re walking the grounds that we wouldn’t be walking if it hadn’t been for all these contributions.”

“I’m going to say their names, I’m going to tell their stories,” Dr. Katrina Thompson Moore said.

To help ensure the contributions and the memory of enslaved people would not be lost, this year Moore coordinated a teacher training workshop for high school teachers of the Jesuit of the Sacred Heart throughout the United States. It is a combination of history, English, religion teachers and administrators sitting through five week sessions on everything from the Jesuit’s role in slavery to anti-racist bias training, something Thompson said is essential.

“It’s important to say their names, it’s important to tell the students stories, to let the students know the complexity of this state that they live in and that St. Louis University, the school they’ve chosen, the school that we say men and women for others, has a complicated history,” she said.

Exploring and putting the pieces together to craft and reconstruct these stories has been at the forefront of much of Harrison’s work as well as all those who are involved in the Slavery, History, Memory and Reconciliation Project. In one story, for example, Harrison helped to piece together the story of a woman named Matilda Tyler.

Engraving depicting the St. Louis University location in Downtown St. Louis. Photo via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

“This is a woman who we think was as a young girl in that second group of people who were forced to come to St. Louis in 1829 and at some point she married a man named George,” Harrison said.

According to Jesuit records, Matilda was first forced to work at the Jesuits’ farm in Florissant, a city in modern day St. Louis County. She was later sent to St. Louis College, which would later become today’s St. Louis University. She and George had a number of children.

“She earned the money to buy herself and her youngest son, Charles, out of slavery and then worked for another almost 20 years to buy the rest of her sons out of slavery,” Harrison said.

Matilda paid $300 in total for her and her youngest son’s freedom which would total to around $9,000 to $10,000 today, as noted in an 1847 entry in the Province Treasury ledger.

“She earned what would today be tens of thousands of dollars to buy her family out of slavery and not only that, but she lived until 1900 and her son Charles, the youngest one, became a fairly prominent politician here in St. Louis,” Harrison said.

For Rashonda Alexander, the gravity of learning the names of one’s ancestors, individuals who survived the atrocity that was slavery, is profound.

“I got chills when she said their names,” she said.

But for Alexander saying their names is two-fold, not only amplifying the names of the enslaved but also calling attention to the names who did the enslaving, something also listed in a list of demands from St. Louis University students in September 2020. At the time students spoke out after someone defaced a memorial for Breonna Taylor on campus. The students then asked for Dubourg Hall, Frost Campus and Verhaegen Hall specifically to be renamed, among other requests.

An early depiction of the St. Louis University in its original location in downtown St. Louis. Photo via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

“I want a lot of truth to be told, not just at the university but for the university in particular, take the names down of the enslavers and put the names up of the enslaved and tell the story,” she said.

This fall, St. Louis University promoted its African American Studies program to full department status, an action that had been years in the making, said Christopher Tinson, department chair of the African American Studies Program at the university. It was also a part of a 2020 list of demands from students as an action to help “sustain success with adequate and financial resources.”

“Since the 1970s we’ve been an institute, a contract major, and then a program with a major and minor. It has taken the university 40-plus years to acknowledge the importance of our work as an independent department with the ability to attract, recruit, hire, and tenure our own faculty members. Since 2000, we’ve graduated over 80 students with a major in African American Studies,” he said.

He went on to say recent events, such as George Floyd’s murder, reignited the fight for the department again and this time “there was positive energy and alignment between the president, provosts, and academic deans that frankly hadn’t been there before now.” He added they are building new courses and working to make sure students know all the department offers sooner rather than later.

This kind of work, descendants say, will need to continue.

“Some of our brothers and sisters will never have the opportunity to know the names, the places, the locations of their ancestors,” Proudie explained.

“With each discovery comes a new opportunity,” she said. “I just want the public to know that and I also want them to know that all we want is to be acknowledged, so be prepared.”

This story has been updated to clarify Fr. Tim Kesicki, SJ’s new title.